NASA’s Juno spacecraft captured the closest view of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa in 22 years

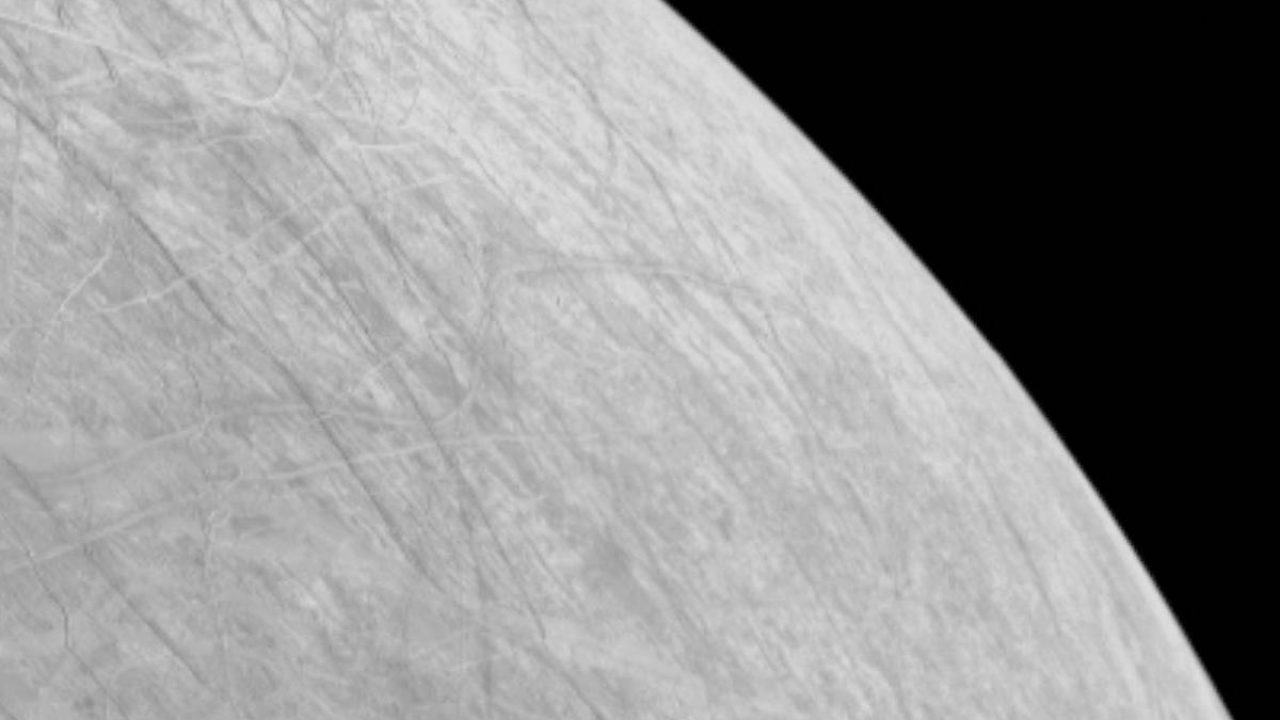

Earth has now received the first image taken by NASA’s Juno spacecraft as it flies past Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa. This image was taken at 2:36 a.m. PDT (5:36 a.m. EDT) on Thursday, Sept. 29, during the solar-powered spacecraft’s closest approach at a distance of about 219 miles (352 kilometers). It reveals surface features in a region called Annwn Regio near the Moon’s equator.

Close-up observations of the icy moon by the Juno spacecraft provide the first close-up of this oceanic world in more than two decades, resulting in remarkable images and unique science.

Earth has now received the first image taken by NASA’s Juno spacecraft as it flies past Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa. This image was taken at 2:36 a.m. PDT (5:36 a.m. EDT) on Thursday, Sept. 29, during the solar-powered spacecraft’s closest approach at a distance of about 219 miles (352 kilometers). It reveals surface features in a region called Annwn Regio near the Moon’s equator.

It is only the third close pass of Europa in history below an altitude of 310 miles (500 kilometers). In fact, this is the closest any spacecraft has taken at Europa since NASA’s Galileo came within 218 miles (351 kilometers) of the surface on January 3, 2000.

Slightly smaller than Earth’s moon, Europa is the sixth largest moon in the Solar System. Researchers have discovered evidence that a salty ocean lies beneath a mile-thick ice shell, raising questions about the possible conditions capable of supporting life beneath Europa’s surface.

This section of the first image of Europa captured by the spacecraft’s JunoCam during this flyby zooms in on Europa’s surface north of the equator. The enhanced contrast between light and shadow seen along the terminator (night boundary) makes rugged terrain features easily visible. These include tall shadow-casting blocks, while bright and dark edges and troughs run across the surface. Astronomers believe that the oblong pit seen near the Terminator may be a damaged crater.

With this additional data about Europa’s geology, Juno’s observations will benefit future missions to the Jovian moons, including NASA’s Europa Clipper. The mission, which will launch in 2024, will study Europa’s atmosphere, surface and interior. Its main science goal will be to determine whether there are life-supporting sites beneath the moon’s surface.

As exciting as Juno’s data would be, the spacecraft only had a two-hour window to collect it. At that time it was traveling at a speed relative to the Moon of about 14.7 miles per second (23.6 kilometers per second), or 53,000 miles per hour (85,000 kilometers per hour).

“It’s very early in the process, but by all indications, Juno’s flyby of Europa was a great success,” said Scott Bolton. He is Juno’s principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “This first image is just a glimpse of the remarkable new science coming from Juno’s comprehensive array of instruments and sensors that captured data from the moon’s icy crust.”

During the flyby, the mission acquired some of the highest-resolution images of the Moon (0.6 miles, or 1 kilometer, per pixel). It also collected valuable data on the composition of Europa’s ice crust, surface composition, interior, and ionosphere. In addition, he collected useful data on the Moon’s interaction with Jupiter’s magnetic field.

“The science team will compare the full range of images obtained by Juno with images from previous missions, looking at whether Europa’s surface features have changed over the past two decades,” said Candy Hansen. She is a Juno co-investigator who leads the camera’s planning at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona. “The Junocam images will fill in the current geologic map, replacing the existing low-resolution coverage of the area.”

Close-up views of Juno and data from its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) instrument, a multi-wavelength microwave radiometer, will provide new details about how Europa’s ice composition changes beneath its crust. With all this information, scientists will be able to generate new insights on the Moon, including data from the search for regions where liquid water may exist in shallow subsurface pockets.