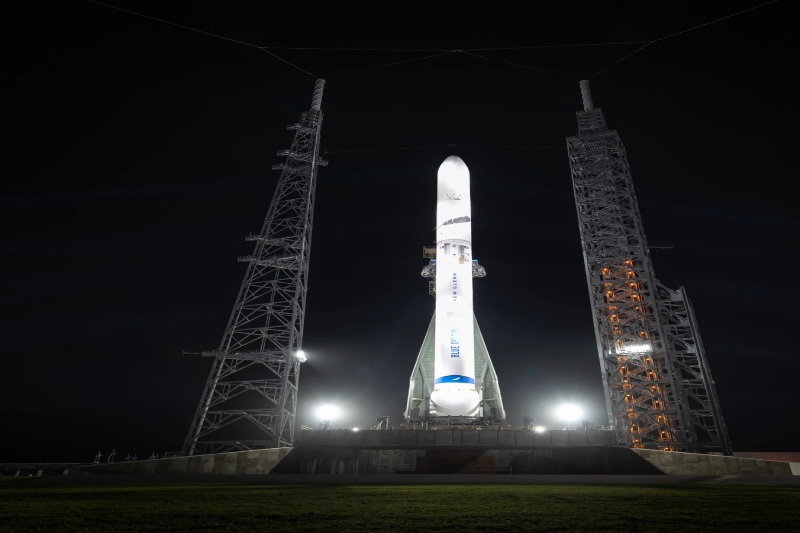

Those who have followed Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket development have been waiting for indications of movement from the typically reticent space corporation. Engineers moved a full-scale New Glenn rocket, which is composed of some flying components, to a launch pad in Florida on Wednesday in order to conduct ground testing.

It’s quite likely going to be at least six months until the first launch from New Glenn, and it could not even occur this year. Observers both inside and outside the space business have become accustomed to the almost yearly pattern of another launch delay at New Glenn during the past few years. The first flight at New Glenn was originally scheduled for 2020, however it was postponed to 2021, 2022, and finally later this year.

Increasing in size

The founder of Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos, was present at Cape Canaveral when his enormous new rocket was first seen launching. Bezos posted on Instagram, saying, “Just incredible to see New Glenn on the pad at LC-36.” “A big year is coming up. Come on, let’s go!”

Blue Origin officials intensified their efforts to fly the first New Glenn test flight by the end of 2024 beginning late last year. This message was sent out at the same time that Blue Origin’s chief executive, Dave Limp, took over from Bob Smith. During Smith’s seven-year tenure, the company launched the first human suborbital flights on its New Shepard rocket. There were also numerous setbacks with the New Glenn rocket during Smith’s tenure as CEO.

Blue Origin is under pressure from Limp to expedite, and it appears that staff members are aware of this. The business moved components of the New Glenn rocket in December from its facility, which is situated right outside NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, to a final assembly hangar at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, which is roughly nine miles away.

The first stage booster, which includes flight hardware, was linked to an upper stage that Blue Origin has reserved for ground testing by technicians within that building. A 23-foot-diameter (7-meter) payload fairing was the last component of the rocket to be fitted. New Glenn’s highest part was made to shield spacecraft during the first stage of flight.

Blue Origin used the transporter-erector arm at Launch Complex 36 (LC-36), a decommissioned Atlas launch pad that Blue Origin took over in 2015, to lift a structure last week that replicated the rocket’s empty mass vertical. The purpose of this was to verify the lifting arm at LC-36 one last time before Blue Origin launched a real, or nearly genuine, rocket onto the pad.

A completely completed New Glenn rocket was moved out of the hangar at LC-36 and up the ramp to the launch pad on Wednesday by ground technicians. Subsequently, the two-stage launcher was elevated vertically by the hydraulic lifting arm. With a height of almost 320 feet (98 meters), New Glenn is one of the biggest rockets ever seen on Florida’s Space Coast. It is almost as tall as the Saturn V utilized in the Apollo program and about the same as NASA’s Space Launch System rocket.

“The upending is one in a series of major manufacturing and integrated test milestones in preparation for New Glenn’s first launch later this year,” Blue Origin officials wrote in an update on Wednesday. “The test campaign enables our teams to practice, validate, and increase proficiency in vehicle integration, transport, ground support, and launch operations.”

Nearly 100,000 pounds (45 metric tons) of payload can be carried into low-Earth orbit by New Glenn. This weight class is below SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy but above the maximum capabilities of the Vulcan rocket from United Launch Alliance and the Falcon 9 rocket from SpaceX for low-altitude orbits. In addition, Blue Origin intends to launch lunar landers for NASA’s Artemis mission to the moon using the New Glenn rocket.

The reusable first stage rocket from New Glenn is intended to land in the Atlantic Ocean on an offshore barge and be recovered by the same means as SpaceX recovers its Falcon 9 launcher.

“The fairing is large enough to hold three school buses,” Blue Origin said. “Its reusable first stage aims for a minimum of 25 missions and will land on a sea-based platform located roughly 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) downrange.”

After 24 years in business, Blue Origin employs about 11,000 people nationwide, with the majority of its workers working in Washington, Texas, Florida, and Alabama. Blue Origin is working on a variety of projects outside of rocketry, such as cargo and human-rated lunar landers for NASA and a space tug that could transport payloads into different orbits for the US military, even though the business hasn’t launched anything into orbit yet. For all these initiatives to work, New Glenn is essential.

The most recent development with New Glenn by Blue Origin coincides with reports that Jeff Bezos’s space company is close to purchasing United Launch Alliance from Lockheed Martin and Boeing.

Difficult circumstances

For Blue Origin, getting New Glenn to the launch pad is a significant accomplishment. Though there is still much to be done before the rocket is prepared for flight, this is definitely a watershed moment for the privately funded New Glenn program.

“Several demonstrations of cryogenic fluid loading, pressure control, and the vehicle’s venting systems” will be the next stage, according to Blue Origin.This specific test vehicle will be loaded by Blue Origin with cryogenic liquid nitrogen, which will act as a substitute for the liquid oxygen and ultra-cold methane propellants that the first stage booster uses during a real launch. This forthcoming Integrated Tanking Test (ITT) will not load the higher stage.

These first tests are primarily intended to confirm that Blue Origin’s launch pad and ground systems operate as intended.

This test vehicle at New Glenn is engine-free. In the coming months, Blue Origin intends to complete testing of the two hydrogen-burning BE-3U upper stage engines and the seven methane-fueled BE-4 booster engines that will take off on the first New Glenn rocket.

Blue Origin should finish the Integrated Tanking Test in a few weeks if all goes as planned. After that, the rocket will roll off the launch pad, enabling technicians to place the seven BE-4 engines in the booster’s engine compartment. Prior to going back to LC-36 for the summer hotfire of the seven BE-4 engines, a milestone Aviation Week stated is planned, New Glenn will also require a new upper stage.

At full throttle, each BE-4 engine can provide 550,000 pounds of torque. The combined thrust of seven of them will exceed 3.8 million pounds. Since the BE-4 engine operated seemingly faultlessly during the inaugural launch of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket last month, Blue Origin can already assert that the engine is flight-proven.

The BE-4s assigned to New Glenn and the BE-4s flown on Vulcan differ slightly in their designs, though. One reason is that, starting with the first New Glenn flight, Blue Origin will try to recover the booster at sea using the BE-4s, which are intended to be reusable from the outset. The BE-4s on Vulcan will be single-use for the foreseeable future, although ULA intends to eventually make its Vulcan rocket somewhat reusable.

According to Aviation Week, Blue Origin’s initial operating strategy is for a rotation of four reusable New Glenn boosters, each of which would fly as frequently as once every thirty days.

Other than saying that New Glenn will appear later this year, the business has not provided a concrete release date. Two small NASA satellites headed for Mars are expected to be carried on the first New Glenn test mission, an agency official stated in November.

Blue Origin has a contract with NASA for the ESCAPADE mission, which is scheduled to launch in August 2024. This schedule is being reviewed, though. Instead of putting the two ESCAPADE spacecraft into an initial orbit around Earth, engineers are considering the option of utilizing New Glenn to send them directly to Mars because of its tremendous lift capabilities, which is excessive for spacecraft the size of a mini-fridge.

A later launch date for ESCAPADE would be possible if the trajectory were to be changed. If Earth and Mars are not in the correct places in the Solar System when the mission launches in 2024, it will have to wait until 2026.

Recall that launchers similar to New Glenn, including SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Starship, ULA’s Vulcan, and Japan’s H3, required a year or two to reach a first flight following the arrival of their first full-scale test vehicles at the launch pad for fueling rehearsals and fit checks. throughout the last stages of a rocket’s development, issues that were missed throughout component testing and manufacture are frequently found.

But according to Aviation Week, Blue Origin’s vice president of New Glenn, Jarrett Jones, is optimistic about flying the rocket this year. “This year is our launch year. It is real, according to Jones. “We intend to launch two times this year.”