‘Outer Space on Earth’ is a Place where NASA’s Europa Clipper Flourishes

NASA plans to launch Europa Clipper in less than six months, embarking on a 2.6 billion kilometer (1.6 billion mile) journey to Jupiter’s ocean moon Europa. It will be an adventure of extremes, from the exhilarating rocket trip to the harsh radiation of Jupiter and the severe heat and freezing of space. To make sure it’s capable of the task, the spacecraft underwent a rigorous battery of testing at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

The series of tests, known as environmental testing, replicates a variety of environmental conditions that the spacecraft would encounter, including shaking, cold, vacuum, electromagnetic fields, and more.

“These were the last big tests to find any flaws,” said JPL’s Jordan Evans, the mission’s project manager. “Our engineers executed a well-designed and challenging set of tests that put the system through its paces. What we found is that the spacecraft can handle the environments that it will see during and after launch. The system performed very well and operates as expected.”

The Gantlet

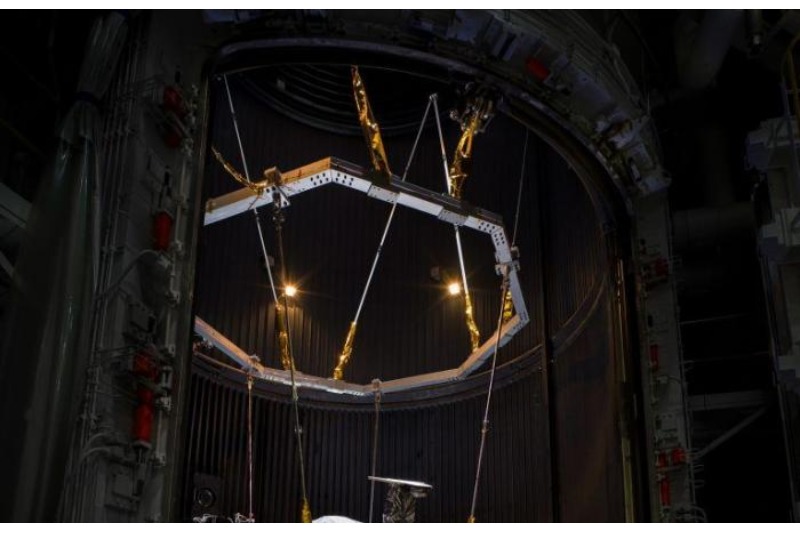

The most recent environmental test for Europa Clipper took sixteen days to perform, making it one of the most complex. The spacecraft is among the largest that has ever fit within JPL’s famed 85-foot-tall by 25-foot-wide (26 meters by 8 meters) thermal vacuum chamber (TVAC), and it is the largest that NASA has ever developed for a planetary mission. Known as the 25-foot Space Simulator, the chamber simulates the airless atmosphere of space by producing an almost perfect vacuum inside.

Simultaneously, engineers tested the hardware under the high temperatures it would encounter when Europa Clipper is near Earth on its sun-facing side. The Space Simulator’s top large mirror reflected beams from powerful bulbs at the simulator’s base, simulating the heat the spacecraft will experience.

The lamps were turned down to a space-like temperature, and tubes filled with liquid nitrogen were inserted into the chamber walls to replicate the journey away from the sun. After then, the crew monitored the spaceship using over 500 manually connected temperature sensors to see if it might reheat itself.

The spacecraft’s electrical and magnetic components were tested to make sure they wouldn’t interact with one another before environmental testing came to an end with TVAC.

Additionally, the orbiter was tested for acoustics, vibration, and shock. The spacecraft was frequently shook during vibration testing, both up and down as well as side to side, just like it will be jostled during liftoff atop the SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. Pyrotechnics were used in shock testing to simulate the tremendous shock the spacecraft will experience when it separates from the rocket to go out its mission.

Last but not least, acoustic testing confirmed that Europa Clipper could tolerate the launch noise, which is so intense that a weak spacecraft could be damaged by the rocket’s rumbling.

“There still is work to be done, but we’re on track for an on-time launch,” Evans said. “And the fact that this testing was so successful is a huge positive and helps us rest more easily.”

Looking to Launch

The spacecraft will be transported to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida later this spring. Teams of technicians and engineers will make last-minute preparations there while keeping a close eye on the time. The launch window for Europa Clipper begins on October 10.

Following launch, the spacecraft will accelerate in the direction of Mars until it reaches a point where it can harness the planet’s gravity to gain further velocity by late February 2025. After that, in December 2026, the solar-powered spacecraft will swing back toward Earth to receive another slingshot boost from the gravitational field of our own planet.

After that, Europa Clipper will go to the outer solar system and is expected to reach Jupiter in 2030. In order to collect data with its potent set of science instruments, the spacecraft will orbit the gas giant while passing 49 times over Europa, coming as near as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from the moon’s surface. Scientists will learn more about the aqueous interior of the moon thanks to the information acquired.